“I’m sorry.”

The two most powerful and humble words to come out of a Leaders mouth. Arguably any mouth!

When done in the right way, corporate apologies can turn around ill will towards a company, and mend a PR catastrophe.

Done badly, apologies can exaggerate issues, and seem dishonest and insincere.

This whole issue is contentious.

From the worlds of politics, sport, music and hospitality, leaders in all of these areas have faced criticism of their brand, services, conduct as an employer or personal conduct which has left potentially disastrous results for their staff, customers, fans and popularity/ success.

Adelle cancelling her Las Vegas concerts faced a backlash for not announcing the cancellations sooner.

Brew Dogs’s James Watt facing contentious claims against his personal conduct to staff

Um, a certain Prime Minister facing tricky questions about his staff and events during the Lockdown.

To try and remain impartial, against current, and very recent, emotional events, we’ve used historical business references to corporate situations an real-life events several years ago.

Here are 10 examples of the most powerful corporate apologies.

These examples show that an open, heartfelt apology can make all the difference and actually improve the business’ brand presence success with their customers.

Adding humour to a corporate error. KFC – not so ‘finger lickin’ good!

When KFC’s most important ingredient went missing (chicken 🍗) and had to temporarily close 900 branches in the UK, angry customers took to social media.

KFC took a risk using humor in their apology in a self-deprecating way.

They took out full-page adverts in the press simply showing their iconic chicken bucket with a re-worked logo:

“FCK.” Paired with a brief explanation of the problem and a promise that this wouldn’t happen again.

KFC saved its brand—and its chicken!

PwC issues apology after Oscars best picture envelope mistake!

(and demonstrate how a corporate company SHOULD apologise!)

It was the mistake seen live around the world: the wrong movie was announced as the Best Picture winner at the 2017 Oscars.

Accounting firm in charge of vote counting vows to investigate error that led to La La Land being awarded by mistake.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accountancy firm that had overseen the counting of the Oscars ballots for 83 years, decided to quickly apologise for the most spectacular of blunders in the history of the starry Oscars ceremony – when the award for best film was mistakenly presented to ‘La La Land’ instead of the actual winner ‘Moonlight’.

PwC promised to investigate the error after Warren Beatty, (presenting the best picture award with Faye Dunaway), ended up with the wrong envelope!

“We sincerely apologise to Moonlight, La La Land, Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, and Oscar viewers for the error that was made during the award announcement for best picture,” PwC said in a statement.

PwC, which was tasked with counting the votes. Instead of making excuses, swiftly and decisively decided to own it’s mistake, offering a short, clear apology.

Their statement briefly explained what happened, apologised to everyone involved, and graciously thanked the people who handled the situation.

Avoiding drawing out an embarrassing situation, PwC took ownership, apologised and moved on.

A great example of the right way for a business to apologise!

Be personal and original. O.B. Tampons Creates 10,000 Personalised Apology Videos!

Perhaps one of the best ways to say sorry, is to sing it. In 2010, a line of O.B. tampons was suddenly removed from shelves due to supply problems.

Customers were outraged!

O.B.’s parent, Johnson & Johnson, sent a personalised apology song to all 65,000+ women in their customer database with their name in the song.

The company created videos for their affected customers which they could and did share easily on social media.

O.B. turned a potential PR disaster into a social media win.

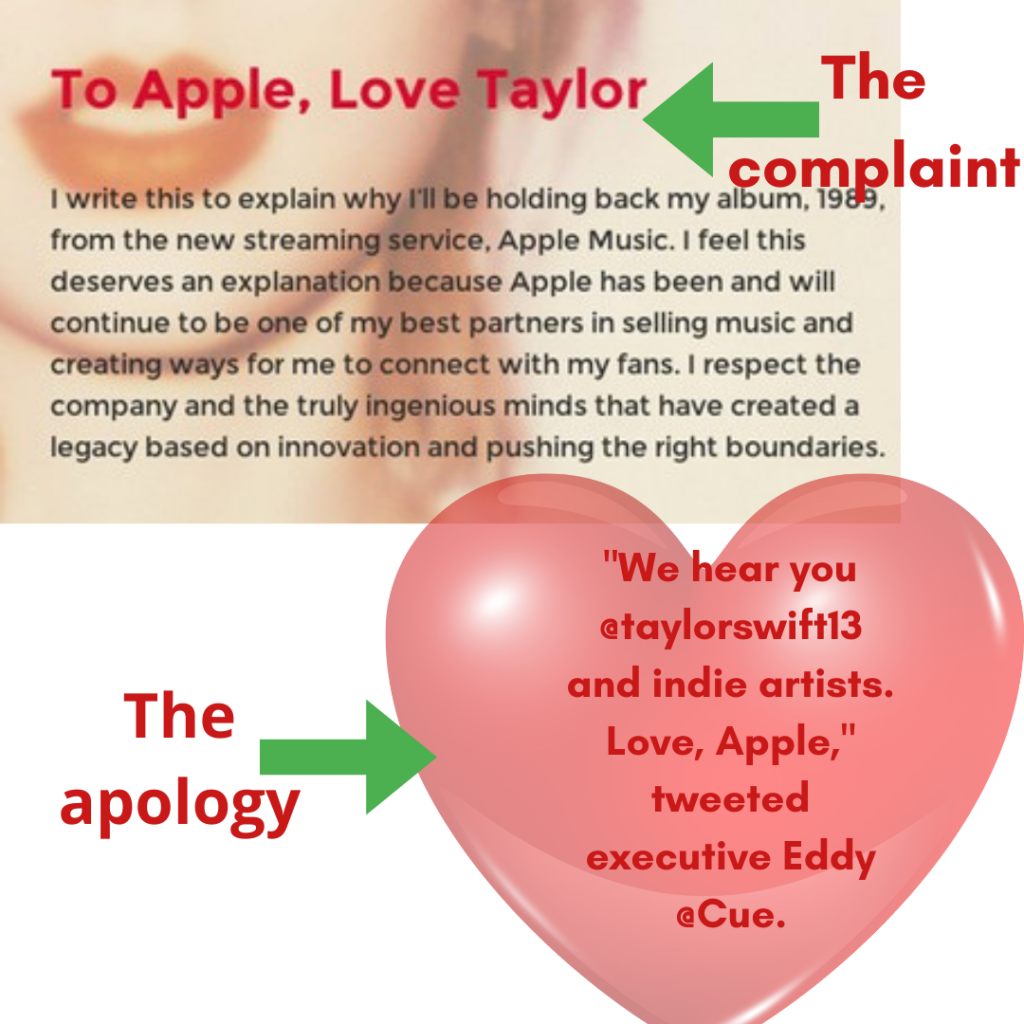

Apple makes ‘swift’ Social Media apology to Taylor Swift!

Anyone who’s listened to Ms Swift’s lyrics, knows it’s not a good idea to get on her bad side. 🤣🤣.

Back in 2015, Apple announced a free 3-month trial period, which sounded great, except that but during that period, any music streamed would not accumulate royalties to pay the artists, labels, or music publishers who produced it!

Whilst indy artists seemed the most upset about the policy, it wasn’t until music-phenomenon Taylor Swift posted to her Tumblr page about her dismay over the agreement that EVERYONE started to listen.

Swift ‘swiftly’ boycotted Apple Music after the service offered three free months to customers without paying artists.

She also posted her news on social media platform Tumblr.

How did Apple respond to a potential PR nuclear bomb?

They diffused things by deciding to respond in kind on Twitter, issuing a full apology, and a statement that they would change their policy and pay artists.

The really clever bit?

Apple’s apology really stood out,

because it was directed

to just one person

on a social media platform

everyone could see.

Face up to your mistakes and admit you were wrong! Airbnb Apologises for lack of Diversity

Airbnb was accused of racial profiling and discrimination in December 2015, with a Harvard paper and social media feeding frenzy to back up the claims.

Instead of dodging the issue, Airbnb proactively addressed the problem with an email from the CEO to all members.

The company took a stronger stance against discrimination with a brand-new policy and followed it up with an audit and inclusion campaign.

JetBlue CEO Offers Raw Video Apology and Promises to Change

One of the worst aviation PR disasters came when JetBlue passengers were stranded on the tarmac for 11 hours with limited updates.

After the fiasco, JetBlue’s CEO shared a raw video with his apology. He also made detailed promises about how the company would prevent similar issues from happening in the future and re-committed to the company’s reputation of strong customer service with the JetBlue Customer Bill of Rights.

Netflix Recognizes Not All Ideas are Good

Back when DVDs were still an important part of Netflix’s business, the company broke into two categories with separate pricing and billing—one for streaming and one for billing. The change meant a price increase that customers weren’t happy about. The CEO was open and honest about the mistake and admitted he had messed up.

His open letter to customers did the trick, and people appreciated that he owned the mistake.

Sony Helps Remedy Data Breach

In 2011, Sony was the victim of one of the largest data breaches in history when the personal information of 77 million PlayStation users was leaked. The CEO apologised personally and acknowledged the frustration the breach had caused. Even better, customers were given a free

month of PlayStation Plus and identity theft insurance to remedy the situation!

Toyota Makes Personal Apology Visible

Toyota’s biggest nightmare happened in 2010, when more than 8 million cars were recalled and nearly 90 people were killed because of accidents caused by the defects.

The CEO offered personal condolences to the families and emotionally, sincerely apologised to all customers.

To make sure everyone got the message, Toyota created an ad campaign admitting they hadn’t lived up to their safety standards and took out adverts in major newspapers about how they would fix the safety issues.

Domino’s Responds to Prank Video with Apology Video

Companies learned the danger of social media in 2009 when a video of Domino’s employees putting cheese up their nose and farting on the salami they used on a customer’s pizza went viral. In a response to the prank video, Domino’s CEO responded with a heartfelt apology video of his own.

His video put a face to the company and outlined the company’s cleanliness standards.

Every situation and apology is different, but these examples show that honest, quick responses can turn an often awful, negative situation completely around.

Taking responsibility and fixing the problem goes a long way in the art of the corporate apology.

But what about Leaders in business? ………

When Should a Leader Apologise—and When Not?

When we hurt a person we know, even if unintentionally, we are generally expected to apologise.

The person ‘wronged’ feels entitled to an admission of error and an expression of remorse/ regret. Rightly so!

We, in turn, as the ‘aggressor’ try to diffuse the situation by saying, “I’m sorry,” and perhaps making restitution.

But when we’re acting as leaders, the stage is different.

Leaders are responsible not only for their own behaviour but also for that of their employees/ teams/ management, who might number in the hundreds, thousands, or even millions!

The first question? Who exactly is the guilty party?

The degree of damage is important to recognise too.

When a leader feels pressured to say sorry, especially for a transgression affecting clients, customers, colleagues or others, the harm inflicted was likely serious, widespread, and long-lasting.

Since leaders speak for, as well as to, their teams, customers, and clients, their apologies have big implications!

The act of apologising itself is carried out not merely at the level of the individual but also at the level of the institution.

It is not only about personally saying sorry, but also political. It is a performance in which every nuance, tone and expression matters.

Each and every word becomes part of public record, especially in today’s culture of social media. Once said, those words are ‘out there’ forever.

A leader’s public apology is a high-stakes strategy, for their business, company, and of course, their people and employees.

Get it right and it can reposition a brand, company and its values amongst its competitors. Get it wrong? Gerald Ratner spring to mind? Ratners? Ratners who?

Precisely.

Hint. For those under 30, Google Gerald Ratner. 🤣.

Dangerously, a leader’s willingness to apologise can be viewed as a sign of strong character or, as a sign of abject weakness.

A successful apology can turn enmity into personal and business success —while an apology that is too little, too late, or too transparently tactical or insincere, can bring on individual and institutional ruin.

Currently there have been recent apologies from the world of politics, to sport to music, with Adelle receiving criticism for leaving her apology too late before cancelling her Las Vegas concerts.

What, then, is to be done? How can leaders decide if, and when to say sorry publicly? And, HOW to say sorry!

Why Apologise Now?

The question of whether leaders should apologise publicly has never been more urgent.

In recent years, an ‘apology culture’ whereby apologies of all types and for all kinds of transgressions are extended far more frequently than before.

In his book On Apology, Aaron Lazare’s book, ‘On Apology’ offers lots of evidence that the number of apologies is generally on the rise.

He points out that they have become grist for our collective mill: Media journalists he says, “covering the national and international scene have written about the growing importance of public apologies, while articles, cartoons, advice columns, and radio and television programs have similarly addressed the subject of private apologies.”

Members of various professions hardly known in the past as pillars of humility, have begun to discuss what role apology plays in their professional practice.

Doctors will now at least consider apologising to a patient for a medical mistake; and within the medical profession generally, there is discussion about when an apology is in order.

Laws have been created to enable medical professionals to apologise to their patients.

Colorado in 2003, instigated a law stating that an apology extended by a health care provider would, in any civil action, “be inadmissible as evidence of an admission of liability.” (Several other US states deem expressions of sympathy inadmissible in court—though for them, full apologies are another matter.)

While, in the past, fear of a malpractice suit nearly always precluded health care providers from admitting a mistake, University of Florida law professor Jonathan R. Cohen observes in “Toward Candor After Medical Error” (Harvard Health Policy Review, Spring 2004), it is “precisely that silence—that failure to admit a mistake and apologise for it—that can prompt a lawsuit.”

The increase of leaders publicly saying ‘Sorry,’ has been especially remarkable.

Apologies are tactics leaders now frequently use in an attempt to put behind them, at minimal cost, the errors of their ways.

So many corporate professionals in business expressed regret for one or another offence in the summer of 2000 that some business writers called it the “summer of apologies.”

The transgressions for which leaders “begged pardon” included unreliable flights, bad phone service, and even tyres blowing out! Since then, the pattern has continued. The CEO of health care IT company ‘Cerner’ insulted his management team in an e-mail; when the company’s stock took a nose-dive, he apologised for the e-mail he’d sent.

Etienne Rachou, head of Air France’s European and North African operations, apologised to an Israeli businessman after an Air France pilot referred to the Tel Aviv destination as “Israel-Palestine.”

John Chambers, CEO of Cisco Systems, asked service providers for their forgiveness because the company hadn’t made their needs enough of a priority.

Sometimes leaders even apologise for errors or misdeeds to which they personally have no connection!

In 2005, Ken Thompson, chairman and CEO of Wachovia, revealed that two of it’s acquired companies had owned slaves. He added: “On behalf of Wachovia Corporation, I apologise to all Americans, and especially to African-Americans and people of African descent. We are deeply saddened by these findings.” In other words, the Chairman and CEO decided to say sorry through association with two businesses that he found out had been wrong in the past!

Leaders outside the corporate world have also done a fair bit of breast-beating.

- Former U.S. secretary of defence, Robert McNamara apologised repeatedly for his poor judgment during the Vietnam War.

- Republican U.S. senator Trent Lott said he was sorry for suggesting that the country would have averted many problems if one-time segregationist Strom Thurmond had won the 1948 presidential race.

- Evangelist Pat Robertson apologised for saying that the United States should kill Venezuela’s president, Hugo Chavez, and for suggesting that the stroke suffered by Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, was ‘divine’ retribution for “dividing God’s land.”

- Oprah Winfrey, cultural and media icon, apologised for defending (and being duped by) James Frey’s “memoir”—for leaving “the impression that the truth does not matter.”

- And Lawrence Summers, the president of Harvard, apologised for suggesting that “intrinsic aptitude” might explain the low number of women in science and engineering. A tad misogynistic perhaps?

The case of Summers is a striking example of the lengths to which leaders will go to say they’re sorry.

Having created an outcry stretching beyond the University’s walls, the then president of Harvard, apologised over and over again.

A few days after the incident, Summers sent a letter to every member of the Harvard community that read, in part, “I deeply regret the impact of my comments and apologise for not having weighed them more carefully.”

At a faculty meeting one month later, Summers said: “I deeply regret having sent a signal of discouragement to people in this room and beyond who have worked very hard for many years to advance the progress of women in science and throughout academic life.”

And in another letter, this one sent to Harvard faculty two days after that meeting, Summers wrote, “If I could turn back the clock, I would have spoken differently on matters so complex…I should have left such speculation to those more expert in the relevant fields. I especially regret the backlash directed against individuals who have taken issue with aspects of what I said.” (Importantly – Summers did not apologise right away, and there is evidence that he did so reluctantly).

Of course, it is impossible to know whether a prompt expression of regret would have stopped the furore that ultimately led to his resignation in its tracks.

“Apologies are like everything else: They reflect the cultures and values of the society, company and teams/ employees in which they are embedded.“

We give you Japan as an example. In Japan, a leader’s apology is not nearly so remarkable a gesture as it is in most other countries.

Japan has been described as the “apologetic society par excellence.”

Still, it wouldn’t be a backlash to say that the apology as a form of social exchange has grown in international importance. While the methods may differ—China actually has ‘apology companies’ that employ surrogates to provide explanations and express remorse—the apology culture is a global phenomenon.

Why Bother Apologising?

Why do we apologise? Why do we, our employers, our companies, ever put ourselves in situations likely to be difficult, humiliating, and even hazardous?

Leaders who apologise publicly are especially vulnerable. As highly visible people, they are expected to appear strong and competent. Whenever they make public statements of any kind, their individual and professional reputations are at stake.

Clearly, then, leaders should not apologise often or lightly.

For a leader to express contrition, there needs to be a good, strong reason.

In Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation, Nicholas Tavuchis writes that apologies refer to acts that cannot be undone “but that cannot go unnoticed without compromising the current and future relationship of the parties.”

Therefore, this general principle would seem to apply: Leaders will publicly apologise if and when they calculate the costs of doing so to be lower than the costs of not doing so.

More precisely, leaders will say sorry if and when they calculate that staying silent threatens a “current and future relationship” between them and one or more key constituencies—followers, customers, colleagues, or the public.

Here’s a big well-known example.

After repeatedly denying and procrastinating for months, President Bill Clinton decided that if he wanted to get back on task, he had no choice but to offer an abject public apology—and a televised one, at that—for having had an inappropriate relationship with Monica Lewinsky.

He began by admitting his involvement with the White House intern.

He went on to say that “it was wrong” and that he deeply regretted having misled the country.

He concluded his prepared statement by telling his wife and daughter that he was ready to do whatever it would take to make things right between them—and by promising to put the past behind him and turn his attention back to the nation’s business.

Clinton’s apology in the Lewinsky affair was intended to repair, or at least start to repair, two different relationships: his relationship with the American people and his relationship with his family.

Taking into account the mood of the times, given the rampant ‘apology culture’, the president concluded that his path to ‘forgiveness and redemption’ was to offer as full and open an apology as the already humiliating situation and nature of has transgression would allow. In this case, Clinton was taking responsibility for his own bad behaviour.

In contrast, when M. Douglas Ivester, chairman and CEO of Coca-Cola in the late 1990s, apologised to his European customers for the company’s slow response to complaints that Coke products were making them ill, he was taking responsibility, or trying to, for his organisation generally.

As can often happen, when people have felt aggrieved, Douglas Ivester made his real mistake at the outset.

First, he and company executives based in Brussels played down the problem. They dismissed as unfounded the widespread complaints of nausea and headaches, insisting instead that Coca-Cola’s drinks did not, nor could they possibly, pose a health hazard. Only in response to the growing public outcry—and, more importantly, to the bans placed on Coke products by the governments of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg—did Ivester give up. Up against the wall, he at last vowed and committed to investigate the problem thoroughly.

And he finally apologized.

Before it was all over, Ivester had declared consumer trust sacred to Coca-Cola, and company executives were described as deeply regretting the problems encountered by their European customers.

Clearly concluding that the greater the number his expressions of remorse, the more likely Coca-Cola would be forgiven, Ivester ended up issuing one of the most elaborate public apologies ever offered by an American chief executive. In Belgian newspaper ads, he said, “I’m sorry” or “we regret” or “I apologise” five times.

Ironically, the best evidence from subsequent investigations is that the reported illnesses were the result of mass hysteria rather than contaminated Coca-Cola. (Many of the children who complained of becoming sick had not drunk Coke that day.) Nonetheless, Ivester’s professional reputation was so

badly damaged by his mishandling of the crisis, he resigned from his position as CEO just two years after assuming the job!

As the examples of both Clinton and Ivester testify, in general leaders apologise only if and when they feel a pressing political need to do so.

Still, there are exceptions to this rule. Sometimes leaders apologise when their self-interest is not immediately at stake—when the only apparent reason for doing so is genuine remorse and regret.

Once again, President Clinton provides a case in point. In 1998, he apologised for the genocide in Rwanda, which had taken place four years earlier, on his watch.

On a brief visit to the Rwandan capital,

Kigali, he expressed regret and remorse for “not act[ing] quickly enough after the killing began,” even though there was no political pressure to say sorry.

For despite the murder and mayhem—Rwanda’s genocide was arguably the most efficient in human history, with 800,000 dead in four months—virtually no one had demanded that Clinton take responsibility.

The president’s apology was, therefore, authentic rather than simply strategic. It was made to assume some responsibility for the wrongdoing and to scold the international community to never again to stand by and do nearly nothing in the face of mass murder, and atrocities.

There are four possible answers, to the question of why a leader would endure the discomfort and assume the risk of offering a public apology.

Apologies can serve four aims:

Individual purpose.

The leader/ employer / company made a mistake or committed a wrongdoing. The leader publicly apologises to encourage followers to forgive and forget.

Company/ Organisational purpose.

One or more persons in the group for which the leader/ employer is responsible made a mistake or committed an error.

The leader publicly apologises to restore the group’s internal cohesion and external reputation.

Inter-group purpose.

One or more persons in the group for which the leader is responsible, made a mistake or committed a wrongdoing that inflicted harm on one or more people externally.

The leader publicly apologizes to repair relations with the injured parties.

Moral purpose.

The leader experiences genuine remorse for a mistake made or a wrongdoing committed, either individually or on behalf of the organisation. The leader publicly apologises to ask forgiveness and seek redemption.

The first three ‘purposes’ are mainly strategic, rooted in self-interest.

The last purpose is primarily authentic: An apology is extended because it is the right thing to do. As a general principle, leaders should apologise only if doing so serves one of these purposes.

Apologising

People speak of “a simple apology,” but there is no such thing.

To acknowledge a transgression, seek forgiveness, and make things right is a complex act.

Apologies are prompted by fear, guilt, and emotion—and by the calculation of personal or professional gain.

They are shaped by culture, context, and gender.

They are base and self-serving or generous and high-minded.

When extended in public, they amount to performances to which different audiences react in different ways.

Moreover, there is a fundamental distinction to be made between an apology offered on behalf of an individual and one made on behalf of a business or organisation.

This distinction really matters in Western culture, where people expect more from the first type than from the second.

Individuals unwilling to apologise when an apology is in order are subject to censure and opprobrium. Institutions, such as large corporations, are not ordinarily bound by this same stringent moral imperative.

So, what, makes a good apology? A full apology. One that’s likely to work.

Above all, a good apology must be seen as genuine, as an honest appeal for forgiveness. Such apologies are usually best offered in a timely manner, and they consist of the following four parts:

- Acknowledgment of the mistake or wrongdoing;

- Full acceptance of responsibility;

- Sincere expression of regret;

- A solemn promise that the offence/ transgression will not be repeated.

In corporate America, the good apology extended by Johnson & Johnson during the Tylenol crisis has taken on almost mythic proportions. Although the case is about a quarter-century old, it is still considered a near-perfect example of what a leader should do when things go wrong.

In 1982, seven people died from cyanide inserted into Tylenol capsules. Although the crisis was brought on by an individual (who was never caught) rather than an institution (Johnson & Johnson), and subsequent evidence indicated that the killer had no relationship whatsoever to the company, James Burke, Johnson & Johnson’s CEO at the time, immediately assumed responsibility for the disaster. People were told not to consume Tylenol products. Production and advertising were halted. And Tylenol capsules already in stores were recalled (at an estimated cost of some $100 million), while company executives worked tirelessly to resolve the crisis.

Burke also went public—appearing, for example, on 60 Minutes—to reaffirm the company’s mission. “Our first responsibility is to our customers,” he said in an early statement, and he wasted no time inviting consumers to return their bottles of Tylenol for a voucher: “Don’t risk it. Take the voucher so that when this crisis is over, we can give you a product we both know is safe.”

In short, given the serious nature of the crisis, Burke extended the virtually perfect public apology.

He promptly acknowledged the problem.

He accepted responsibility.

He expressed genuine concern.

And he put his money where his mouth was: Not only did he offer to exchange all Tylenol capsules already purchased for Tylenol tablets; he promised new, secure packaging to make certain that the problem would never be repeated.

Marketing experts had speculated that it was very likely the Tylenol brand would not survive—but they were wrong!

Within a year, Tylenol (in tamper-resistant packaging) had regained 90% of its market share.

If anything, both the company and the brand emerged from the crisis with their reputations enhanced.

As Burke’s response to the crisis confirmed, promptness and appropriate timing are important components of a good apology.

Let’s look at the case of Exxon (now Exxon Mobile), which was notoriously lazy in apologising for the effects of the Exxon Valdez’s disastrous oil spill along the coast of Alaska in 1989. The pristine natural environment spoiled with countless deaths of animals and damage to the environment.

The company’s initial response to the crisis?

Silence. Utter silence.

Then CEO Lawrence Rawl, waited six days to speak to the media, refusing to visit the scene of the spill until nearly three weeks after it happened.

In fact, Rawl never fully acknowledged the extent of the disaster.

Exxon’s official statements to the public were weak and inconsistent. By the time Exxon did finally extend an apology of sorts, in a print ad, it was too little too late.

This slow, inadequate response to the disaster cost Exxon dearly. Customers cut up Exxon credit cards and refused to buy Exxon products, and the company was ultimately obliged to pay vast amounts of money in fines and reparations: $2.5 billion to clean up, $1.1 billion to cover the

various settlements, and another $5 billion to compensate for recklessness.

Its refusal to acknowledge its role in an environmental disaster left a stain on its reputation that persists to this day.

The point is, good apologies usually work! Bill Clinton’s apology for his relationship with Monica Lewinsky did finally enable him to neutralise the media feeding frenzy and allow him to better focus on his job as president of the United States.

What’s more, apologising did not hurt him one jot in the polls: –

At the end of his presidency, his job approval rating remained high, at 66%.

Not for nothing was he known as the ‘Teflon President’.

Similarly, John Chambers, Vicente Fox, Pat Robertson, Lawrence Summers, and others who stumbled were either forgiven as soon as they apologised or, at least, given the opportunity to move on.

It is usually the case that when leaders publicly offer apologies that are timely, genuine, authentic and good, those apologies have a positive effect.

There is no evidence of a genuinely authentic apology that backfired.

Refusing to Apologise

Given the advantages of public apologies promptly and properly given, why do leaders so often refuse to apologise, even when a public apology seems to be necessary?

Their reasons can be individual or institutional.

Because leaders are highly visible, their public apologies are likely to be personally uncomfortable and even professionally risky.

Leaders may also be afraid that the admission of a mistake or ‘wrongdoing’ will damage or destroy the group or business for which they are responsible.

Especially if there is the threat of lawsuits!

There can be good reasons for hanging tough in tough situations, as we shall see, but it is a high-risk strategy.

In times of crisis, the instinctive reaction of corporate/ business leaders in particular is to deny, and then to deny again.

Executives are disinclined to admit to a problem, often even veering in the other direction.

Jeffrey Skil-ling insisted he was “immensely proud” of what he had accomplished at Enron; and once upon a time, Martha Stewart called allegations that she was guilty of insider trading “ridiculous.”

Of course, denials like these are often the work of lawyers who insist that their clients stonewall, to stop an apology being considered an admission of guilt.

But, it’s risky to insist on innocence when the evidence is obviously to the contrary.

Bridgestone/Firestone and Ford provide a notorious example. Their problems began in February 2000, with a televised report of fatal rollover accidents involving Ford Explorers equipped with tires made by Bridgestone/Firestone.

Product liability cases are not uncommon in the US or elsewhere globally, but they don’t usually involve, as did this one did, more than 115 deaths.

As a result of the tsunami of complaints that came as soon as the problem was made public, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration started investigating Firestone in May 2000.

Three months later, the pressures were such that the company gave in and issued a recall.

But the fact that executives at Bridgestone, the parent company, remained for several weeks all but inaccessible to inquiries, and then stonewalled for months, badly exacerbated the situation, especially since the media stayed with the story, featuring personal tales of tragedy accompanied by lurid photographs of crashed vehicles.

In September 2000, corporate leaders from both Bridgestone/Firestone and Ford were called to testify before US Congress.

However, instead of using the occasion to win over the huge audience—all three major TV networks led with the story on their evening newscasts—executives from both companies came across as being less than open and honest.

Moreover, they remained entirely unapologetic, appearing more determined to play down the problem than to confront it.

The story ended badly for Bridgestone/ Firestone and Ford. The public relations disaster was so toxic and the fear of legal action so great that both companies finally decided they had no choice but to apologise.

Shortly after the appearance in Congress, Masatoshi Ono, then CEO of Bridgestone/Firestone, told the Senate Commerce Committee, “As chief executive officer, I come before you to apologise to you, the American people, and especially to the families who have lost loved ones in these terrible rollover accidents. I also come to accept full and personal responsibility on behalf of Bridgestone/Firestone for the events that led to this hearing.”

(Later, during a deposition in Nashville, Ono testified that his apology was not to be construed as an admission of fault. To forestall legal liability, he said he had done no more than express sympathy.)

Some time after this, Ford followed suit. Throughout the crisis, then-CEO Jacques Nasser had insisted that Ford was not to blame: “This is a tyre issue,” he claimed, “not a vehicle issue.”

But in the end, the company’s stance softened. Attorneys for Ford settled a lawsuit with, and extended a well-publicised apology to, a woman who had been paralysed in an accident involving a Ford Explorer mounted on Firestone tires.

Like Bridgestone/Firestone, though, Ford said it’s apology did not constitute an admission of fault or legal liability.

Of all the recent refusals of corporate leaders to apologise, perhaps none is more striking than that of Raymond Gilmartin, CEO of Merck from 1994 to 2005.

Merck’s business performed well during the first half of Gilmartin’s tenure, but it stumbled badly.

On the last trading day of 2000, Merck shares closed at $88.61; on Gil-martin’s last day at the helm, May 5, 2005, the stock closed at $34.75.) Notably, Gilmartin’s last months were clouded by what at the time threatened to be a calamity: some 7,000 lawsuits against Merck, involving the use of its painkiller Vioxx.

The New York Times observed that as the company’s Vioxx crisis deepened—the drug had recently been linked in FDA research by David Graham to up to 139,000 heart attacks or deaths arising from cardiac causes—Gilmartin appeared to freeze. Not only did he not apologise; he could hardly bring himself to confront the issue.

And when he eventually did, he was defensive. He insisted that Merck had demonstrated “consistent and rigorous adherence to scientific investigation, transparency and integrity,” and he attacked his opponents for disseminating “incomplete and sometimes inaccurate information.” When Gilmartin resigned—earlier than planned—he left without in any way assuming responsibility or expressing regret. Which raises the following questions: Why might Gilmartin have decided to hang tough—and was it the right decision?

There is the possibility that Gilmartin did not apologise simply because he honestly believed he had nothing to apologise for.

Or, perhaps he did not apologise because every time a leader publicly apologises for anything other than personal misconduct, one constituency is being served—but only at the expense of another.

Merck is a big company, and an apology by Gilmartin might well have implicated other members of the company.

In situations like these, loyalties are at stake, and so is self-interest.

“A leader who fails to stand firm risks losing support among their rank and file and even total control of the situation.“

Alternatively, Gilmartin may have concluded that admitting to even a single mistake would leave his own reputation in tatters.

From these many examples, leaders typically apologise publicly only if and when they calculate the costs of doing so to be lower than the costs of not doing so. Ignoring/ stonewalling, then, is common.

Finally, Gilmartin might have determined that admitting to even one single mistake would leave the company vulnerable—to the exigencies of the marketplace, to the ambitions of competitors, and to the attacking instincts of a litigious society.

It is, of course, impossible to know what would have happened had Gilmartin acted differently; had he decided to express some measure of responsibility and contrition.

But with the benefit of hindsight, Raymond Gilmartin’s approach doesn’t seem to be a wise one. His last five years as CEO were obviously dismal.

They constitute a record for which he did not and could not escape blame. Moreover, others in the company—for example, scientists who suspected that Vioxx could be unacceptably risky but who chose to stay silent—are proving vulnerable as well. Perhaps most telling is the fact that Gilmartin failed to keep the floodgates of lawsuits closed and, may well have helped to pry them open.

As it turns out, there is evidence that ‘stonewalling’ is not necessarily smart even in the most potentially litigious situations.

Ameeta Patel and Lamar Reinsch of Georgetown University concluded in their study of corporate apologies, that the folklore about the legal consequences of apologies is simplistic and misleading, to the detriment of all concerned.

They discovered that apologies can make positive contributions, even “to the apologists’ legal strategy.” Conversely, the evidence suggests, the refusal to apologise —the unwillingness to accept any responsibility or to express any remorse for situations in which there could clearly be some responsibility —can get leaders and their followers into trouble.

It can safely be presumed that by refusing to apologise, Gilmartin and his successor, Richard T. Clark, were following the advice of company lawyers, who warned that Merck had no choice but to keep quiet.

It’s a notorious and tragic chapter of corporate culpability and deceit that affected thousands of lives, jobs, and families. It’s hard to think things could have been worse if Gilmartin in particular had assumed some responsibility for the Vioxx crisis and expressed some regret.

Saying Sorry—Selectively

Apologising in public is not easy, especially for business leaders, or anyone in a leadership position. They are superheroes when things go right—and scapegoats when things go wrong. The buck stops with them.

Public apologies given by corporate leaders are not, even under the best of circumstances, without risk to their companies.

Several experts have warned of the possible downsides. Mary Frances Luce, a marketing professor at Wharton, points out that while apologies can moderate customers’ anger, they can also strengthen the negative associations between the brand and the problem.

Her colleague Stephen Hoch suggests that since firms tend to deal with a heterogeneous group of customers, a mass apology can be risky simply because not everyone requires an apology.

Hoch comments that large numbers of customers are likely not even to know about the problem, so when a company apologises for it’s ill-judged or illegal behavior, some will say, “..that’s a surprise, I didn’t know you were doing that kind of stuff.”

And Chris Nelson, a vice president of the global public relations firm Ketchum, cautions that unless apologies are extended wisely and well they, “might only ensure that the company will face huge legal judgments.”

He goes on to say, “That’s a shame because proper communications often can drain significant amounts of public animosity from a situation.”

Which is precisely the point. 😊

Even those who advocate careful caution agree that a good apology made in a timely fashion is more likely to defuse a bad situation than to make things worse.

There is more subjective, anecdotal evidence, rather than proven hard data on what exactly apologies accomplish.

Despite this, academic research conducted does suggest that leaders are prone to overestimate the costs of apologies and underestimate the benefits.

We know that apologies often soften the ire of those injured or who felt wronged. In a British study of malpractice patients, 37% said they would never have gone to court in the first place had an explanation and an apology been extended.

Similarly, a study conducted at the University of Missouri showed that contrary to the conventional wisdom—which is that a defendant in court is smart to avoid an admission of guilt—full apologies are more rather than less likely

to result in quick settlements of lawsuits.

In fact, the more severe the injury, the more important the apology is to a resolution of the conflict.

Robert Rotberg, former director of Harvard University’s Program on Intrastate Conflict and Conflict Resolution, studied South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

He concluded that apologies can create the possibility of closure in even the most extreme postconflict situations advising;

“The delivery of apology from a dominant side to an aggrieved minority, or from each or all of the contenders mutually, can calm long roiled waters and greatly assist in effecting a successful transition.”

President George W. Bush—initially, anyway—took the opposite approach in fielding criticism about the war in Iraq.

Whatever your position on whether the US should have invaded Iraq to begin with, and whatever your position on how the reigning party at the time handled the conflict since then, you were probably struck by President Bush’s long-standing refusal to admit to anything more than a single “miscalculation,” particularly during the postwar period.

Silence can be defining and defining.

This, in the hindsight headlights of a war that was longer, messier, and bloodier than anyone in the administration had predicted—and in light of a series of scandals, including those involving torture, for which only a few seemes to have been held accountable.

No one knows what could have happened had the president been more willing to acknowledge the problems in Iraq earlier.

Clearly, Bush as POTUS, was betting that time was on his side—that if he held out long enough, events would turn in his favor. But his stubborn, rigidly held opinion that you can’t lead the world if you say you made a mistake (to paraphrase Georgetown University linguist Deborah Tannen), didn’t result in the outcome he’d hoped for.

The situation in Iraq remained unstable at best, and the president’s approval ratings, which translate into his capacity to govern effectively, suffered a steep decline.

In short, the cost of President Bush’s insistence that he appear immune to human error was high—which explains why, in a series of public appearances toward the end of 2005, Bush finally was more open and honest.

Whilst he did not go so far as to apologise, he did specifically acknowledge and assume responsibility for several mistakes. (Almost immediately thereafter,

the president’s approval ratings went up, five points in some polls, seven in others.)

Wall Street Journal columnist Carol Hymowitz asked, “Is it suicidal to admit publicly that things haven’t gone as expected and own up to mistakes? Or should business leaders always appear confident, even invincible?”

There are no strict rules on dealing with matters of the human psyche, but by looking at both hard data and anecdotal evidence, some guidelines can be put together for when and how a leader should make a public apology.

Remember, a public apology should serve an important individual, institutional, intergroup, or moral purpose.

That being said, if the problem/ issue/ offence is institutional rather than individual, the top leader (the CEO, for example) is not necessarily the best person to extend the apology.

Sometimes the organisation/ business is better served if someone further down the corporate ladder acknowledges the problem and expresses regret.

In other words, leaders of groups and businesses should consider apologising publicly only if and when a critical interest is at stake, and only if and when they’re the only ones who can do the work that needs to be done.

How best to say sorry depends on the circumstances.

A full apology includes acknowledgment of the issue/ offence, acceptance of responsibility, expression of regret, and a promise not to repeat the transgression.

But sometimes a partial apology—for example, the acceptance of responsibility or an expression of regret—is better than nothing. While apologies generally should follow hot on the heels of the wrongdoing, lest the offending individual or institution be viewed as avoiding blame or as begrudging in its atonement, there are situations—for instance, when large numbers of people have suffered—in which haste makes waste.

Even when an apology is too late, though, it doesn’t have to be too little.

When doctors at Duke University Hospital made the catastrophic mistake of transplanting the wrong heart and lungs into a 17-year-old girl, who subsequently died, the hospital’s immediate response was to say nothing.

According to reports, the hospital might not have owned up to the problem at all had it not been for the avalanche of bad publicity.

But, once the decision was made to come clean, Ralph Snyderman, then CEO of the Duke University Health System, did so openly and honestly.

No fewer than nine press releases were issued in five days, and Snyderman agreed to be interviewed on 60 Minutes.

On camera, Snyderman admitted the mistake, took responsibility, expressed remorse, and vowed that the hospital would do everything it could to preclude such a calamity from ever happening again.

Once he came forward, Snyderman was able to defuse the situation and resolve the crisis in a way that, under the circumstances, was deemed satisfactory by all concerned. (A few months later, the hospital also agreed to establish a $4 million fund for Latino paediatric services,

in memory of the girl who died.)

Here’s an important leadership lesson: In crisis situations particularly, a less-than-perfect apology is often better than no apology at all.

Even so, a good apology will yield better results than a bad one—and “good” has everything to do with selectivity.

Given everything discussed so far, when should a leader apologise?

- when doing so is likely to serve an important purpose

- when the transgression is of serious

nature

- when it’s appropriate that the leader assume responsibility for the error/ offence

- when no one else can get the job done

- when the cost of saying something is likely lower than the cost of staying nothing

Unless one or more of these conditions exists, there is no good reason for leaders to apologise.

An apology that is misguided or ill-conceived can do more harm than good.

When an apology is obviously expected and assumed, even a partial apology is likely to help both leaders and their teams.

Similarly, when an apology is called for but none is given, anger and hurt can grow and fester, with problems potentially escalating.

5 years after an infamous merger was put together, Joseph Nocera, a business journalist for the New York Times, was still attacking Stephen Case and Gerald Levin for the merger of AOL to Time Warner.

He criticised a failure in taking responsibility. Wouldn’t Case be more credible, Nocera mused, “if he could just bring himself to say he was sorry” for putting together the “merger from hell, has Levin ever apologised for his role in bringing about the dumbest merger of the modern age? I must have missed it.”

Most apologies are motivated by self-interest. But the reason they matter is because, ultimately, they serve a larger social/ community purpose.

When leaders apologise publicly, whether to or on behalf of their employees, teams or clients, they are engaging in what Tavuchis calls a “secular rite of expiation,” which cannot be understood merely in terms of expediency.

The attempt in of itself to come clean is more than an explanation and more than an admission: It is an exchange in which leaders and their audiences attempt to engage in order to move on.

It is in turn this transition, from the past to the future, that enables the course correction that mistakes, and wrongdoing needs to happen.

What does the ‘Perfect Apology’ need to do?

- Acknowledges the mistake or error

- Accepts responsibility

- Expresses regret

- Provides assurance that the offense won’t be repeated

- Is timely

A Framework for Apologies

When you or the people you lead mess up, it’s not easy to decide whether or not to apologise publicly—or to determine how best to do so.

There are a few questions that can help your approach.

What function would a public apology serve?

- Are you or your business/ team right? If yes, could issuing an apology serve your interests anyway?

- Are you or your business/ team wrong? If yes, could issuing an apology get you/ your business out of a difficult situation?

Ask yourself, “Who would benefit from an apology?”

- You personally?

- Your business/ employees/ clients more generally?

- Other individuals, peers and organisations you relate to?

Why would an apology matter?

- For strategic reasons?

- For moral reasons?

Ask yourself; “What happens if you apologise publicly?”

- Will an apology calm the injured parties and speed the way to a resolution?

- Will an apology further incite the opposition?

- Will an apology affect your legal culpability in the eyes of the law?

Mitigation: What happens if you don’t apologise?

- Is time on your side—will the problem likely fade?

- Will your refusal to apologise (or your refusal to do so promptly) make an already bad situation worse?

Ultimately, you need to measure how important your own moral compass is to do the right thing for you as a leader, your staff and your business, against what your business stands to lose if you don’t say sorry.

No easy thing – but that’s why you’re a leader.