In 1666, around 800 Derbyshire people chose to sacrifice themselves, in order to save the lives of thousands of strangers. Could you have done that?

Let’s step back in time to 1665.

Why is the small, Derbyshire village of Eyam significant? In the words of a Victorian local Historian William Wood…

“Let all who tread the green fields of Eyam remember, with feelings of awe and veneration, that beneath their feet repose the ashes of those moral heroes, who with a sublime, heroic and unparalleled resolution gave up their lives, yea doomed themselves to pestilential death to save the surrounding country. Their self-sacrifice is unequaled in the annals of the world.”

Eyam, lies between Buxton and Chesterfield, just north of Bakewell in the Peak District. Most of the villagers were farmers. In the early 1660s, it was a typical, rural, farming community like hundreds that lined the trade routes from London to the rest of England. There were also tailors, bakers, and shopkeepers whose work ensured the livelyhoods of the villagers. And yet in 1665 Eyam became one of the most important villages in the whole of England. The bravery of its 800 souls had huge significance and influenced the development of treatment of the plague and in implementing quarantines successfully.

1665-6 was the last major epidemic of the plague to occur in England, with London the worst affected.

Back then, in 1665, evacuating the capital, the wealthy (Including King Charles II) escaped to their country estates, whilst the authorities did little to help those in poorer communities. Having to fend for themselves, the poor and uneducated of London faced a cruel and horrific foe. The House of Lords eventually discussed the crisis the following year, deciding instead of measures and aid to help, that the policy of shutting up’ of infected individuals with their household would not apply to persons of ‘note’ and that plague hospitals would not be built near to the homes of the wealthy. This selfish and callous attitude added to the feeling of abandonment for many of the poor left helpless and scared in London.

The movement of the rich plus the normal trade routes of England meant that the great plague spread quickly across the country. Rural areas that could previously have been safe from the diseases of urban city areas became exposed.

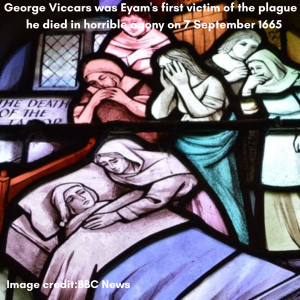

This was the backdrop, heralding the plague’s arrival in Eyam in late August 1665 via a parcel of cloth from London. Delivered to the home of Eyam’s tailor, Alexander Hadfield. His assistant George Vic shook & spread the damp cloth out by the fire to air it, only to find it infested with fleas. His death was recorded in the parish register on 7th September 1665 just a couple of days later.

The plague was spread by infected fleas from small animals and human lice. The bacteria entered the skin through a flea bite, traveled via the lymphatic system to a lymph node causing it to swell. Then characteristic buboes (pus-filled boils) would typically appear under the arm, neck, or groin area. Combined with fever, spasms, black bruising under the surface of the skin, and vomiting, the plague was a truly terrifyingly ferocious and contagious disease.

Back in the 17th Century, many wild causes for pestilence were put forward, from punishment by God to bad air quality. Some thought fragrant herbs would ward off the disease.

Windows and doors were closed and many, especially watchers and searchers in plague hit London, would smoke tobacco. Large piles of foul-smelling rubbish were also burned.

While these methods helped indirectly, for example ridding the city of rubbish meant that the rats spreading the disease had to move on for a reliable food source. Many had limited to no effect.

However in Eyam, a small Derbyshire village, they acted in a unique way. Their intention was to act decisively and prevent the spread of disease.

How?

The Church’s dominance in the 17th Century was still supreme, even after the religious roller-coaster of the Tudor period. The local Reverends were pillars of the community, often the most educated people in their towns and villages.

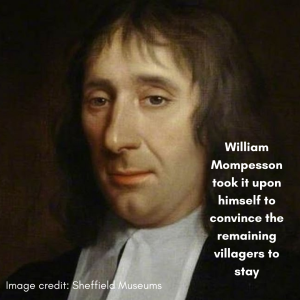

Eyam had two Reverends. Thomas Stanley had been dismissed from his official post for refusing to take the Oath of Conformity and use the Common Book of Prayer. His replacement, Reverend William Mompesson had worked in the village for a year. Aged 28, Mompesson lived in the rectory with his wife Catherine and their two small children. Both husband and wife were highly educated, and it was the actions of Stanley and Mompesson that resulted in the outbreak of plague in Eyam being contained to the village and not spreading to the nearby cities and beyond.

A three-point plan was established and agreed with the villagers. The most important part of this was the setting up of a ‘Cordon Sanitaire’ or quarantine. This line went around the outskirts of the village and no Eyam resident was allowed to pass it.

Signs were erected along the line to warn travelers not to enter. During the time of the quarantine, there were almost no attempts to cross the line, even at the peak of the disease in the summer of 1666.

Eyam was not a self-supporting village. It needed supplies. To this end, the village was supplied with food and essentials from surrounding villages. The Earl of Devonshire himself provided supplies that were left at the southern boundary of the village. To pay for these supplies the villagers left money in water troughs that were filled with vinegar. With the limited understanding they possessed, the villagers realised that vinegar helped to kill off the disease.

Mompesson’s well on the village boundary was used to exchange money for food and medicine with other villages.

Other measures taken included the plan to bury all plague victims as quickly as possible and as near to the place they died rather than in the village cemetery.

They were correct in their belief that this would reduce the risk of the disease spreading from corpses waiting to be buried. This was combined with the locking up of the church to avoid parishioners being crammed into church pews. They instead moved to open-air services to avoid the spread of the disease.

The village of Eyam, while undoubtedly saving the lives of thousands in the surrounding area, paid a heavy price.

At 40%, they suffered a higher death toll than that of London. 260 Eyam villagers died over the 14 months of the plague out of a total population of 800. 76 families in that rural community, lost souls to the plague.

Whole families were wiped out completely.

However, the impact on medical understanding was significant.

Doctors realised that the use of an enforced quarantine zone could limit or prevent the spread of disease.

The use of quarantine zones is used in England, and around the world to this day in the current COVID-19 pandemic, and many other infections, to contain the spread of diseases.

Sadly, back in the 1600s, it took longer for the ideas of quarantine so successfully implemented in Eyam to filter through to become common practice in hospitals back then.

Florence Nightingale, raised in Derbyshire, pioneered the use of isolation wards to limit the spread of infectious diseases in hospitals during the Crimean war. Echoes of the practices put in place at Eyam.

Adopted in hospitals the world over, learning quickly that to contain the spread of diseases, isolation wards needed to be used.

Other lessons on disease control were learned by doctors from the methods used at Eyam included: –

Limiting contact and potential for cross-contamination.

- Eyam villagers paid for food supplies by dropping coins into pots of vinegar, preventing money from being directly handed over.

- Echoed today with cashless payments, sterilisation of equipment, and medical clothing.

- Before COVID-19, lessons learned from Eyam had been seen in the handling of the Ebola epidemic in Africa. The quick disposal of bodies close to the immediate area of death had limited the risk of spreading the disease.

While the events at Eyam did little to change attitudes immediately back then, history has shown how the people of Eyam, shone a beacon of light to scientists, doctors, and the medical world.

They came to use Eyam as a case study in the prevention of disease, and save countless lives ever since.

A fascinating story of how ordinary people with everyday jobs and lives, inspired medical practices used to this very day. And, it is an amazing, moving story of how people from all professions, trades, and backgrounds came together as a community and made a huge difference in the way we manage the spread of disease.

For more information and interesting facts click HERE to a BBC article on the bravery of Eyam’s villagers.

An article by Mary Maguire

Managing Director

Astute | Accountancy & Finance | HR | Office Support

Suite One, Ground Floor West, Cardinal Square, 10 Nottingham Road, Derby, DE1 3QT

T: 01332 346100

M: 07717 412911